Stephen Dock, Our day will come

The Irlande du Nord (Northern Ireland) exhibition opening on 22 May 2022 at the Musée Nicéphore Niépce in Chalon-sur-Saône features photographic work by Gilles Caron and Stephen Dock.

Fifty years after the events of Bloody Sunday, the exhibition proposes a dual photographic perspective, historic and contemporary of the Northern Irish situation.

The Northern Irish conflict, usually referred to as “the Troubles”, started in 1968. It tore the Irish apart, with Republicans and Nationalists (mainly Catholics) on one side and Loyalists and Unionists (mainly Protestants) on the other. The situation deteriorated as paramilitary groups in both camps stepped up their campaigns.

The first part of the exhibition is devoted to the work of Gilles Caron. Present in Londonderry on 12 August 1969, he recorded the first riots and witnessed the country’s descent into a civil war that would last for thirty years. Beyond the iconic images already seen in the press, the exhibition features a set of seventy photographs, both vintage and modern prints, as well as enlarged reproductions of contact sheets that give an insight into the photographer’s working method.

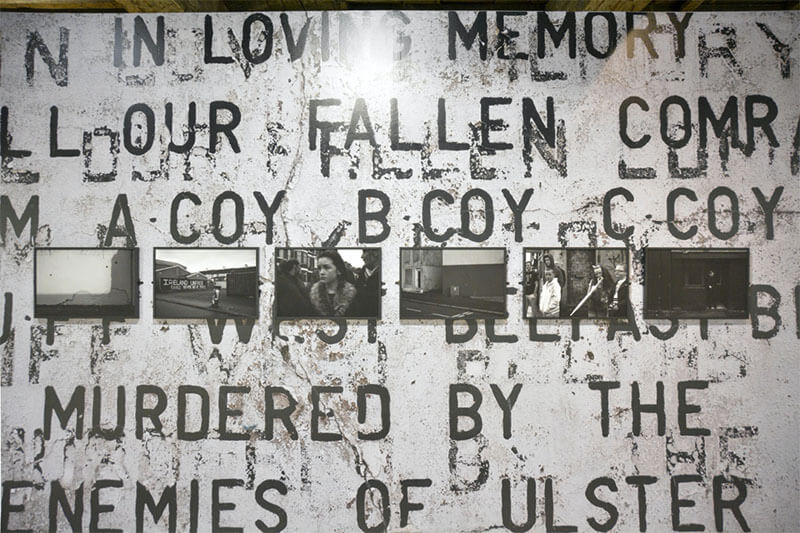

The second part of the exhibition entitled “Our day will come” is devoted to the work of Stephen Dock. Forty years after Gilles Caron, the young photographer went over to Northern Ireland. He went to the same places – Derry, Belfast. Although a peace agreement was signed in 1998, he found that society was still divided and that traces of the Troubles still persist.

Our day will come. This was a popular Republican in Northern Ireland, which refers both to the hope for freedom and to the desire to defeat the other community. But is also impossible to read those words without thinking of the day our own death will come.

Stephen Dock trained in photojournalism at a young age. In 2008, aged just twenty, he already wanted to seize events. To inform the public, he follows the news, often skirting close to danger. Syria, Palestine, Mali, Iraq… His preferred stalking grounds are war zones – conflict his daily bread. But very quickly, faced with his position as a powerless witness and with the limits of photography, Stephen Dock started to question what he was doing: deep down his fascination with battlefields reflects a personal suffering, an inner conflict. In his reports we detect a reflection on his own condition, an inability of the photographer to live in peace. That led him to take another path. Now in his different series, black and white and colour co-exist, details are enlarged, recomposition is possible. The writing is more poetic, the approach more personal. With photography, it is possible to talk about the world and oneself. 2012, the New IRA was formed in Northern Ireland. Stephen Dock decided to go to Belfast on the occasion of the centenary of the Ulster Covenant celebrated by the Unionists. The tension was palpable, but nothing happened. The days of armed combat are over. The Good Friday Agreement that ended thirty years of civil war was signed in 1998. But not all souls have been appeased, and former belligerents cohabit in a fragile peace. In both camps violence, cultural, social and political, inhabits and haunts individuals. It marks the faces of the survivors and the new generations. Its grip even stronger than that of physical violence, it shapes behaviours, is enshrined as an invariant that is passed down from generation to generation. And if hatred between communities has shaped the Northern Irish identity, it has also left a lasting mark on the urban landscape. Life is organised around “peace lines” and “peace walls” which went up in August 1969. In the towns, they form barriers separating the inhabitants of the same neighbourhood, sometimes even the same street. The stigmata of war are everywhere. Huge murals pay tribute to “heroes”, painted messages inform visitors that they are entering Republican or Unionist territory. Walls speak. Graffiti claims adherence to dissident groups, declares support for prisoners or bears witness to a feeling of being colonised: “Brits out!”

The year is punctuated by parades and bonfires, when the Irish flag or the Union Jack is burnt on top of stacks of pallets that can reach heights of thirty metres. Every event is eminently political and refers to partition. The divisions run deep and affect the smallest details of everyday life. So how is it possible to photograph this latent conflict that has been simmering between two communities for hundreds of years? How to represent such a deeply divided society in pictures? To answer these questions Stephen Dock has been to Northern Ireland eleven times in six years. The photographer observes and tries to understand this inability to find peace that he has himself felt. He has built up a photographic corpus consisting of material and signs from the everyday environment: portraits, architectural details, street scenes, and so on. The traces, sometimes barely perceptible, left by the troubles are picked out and made visible by the photographer.

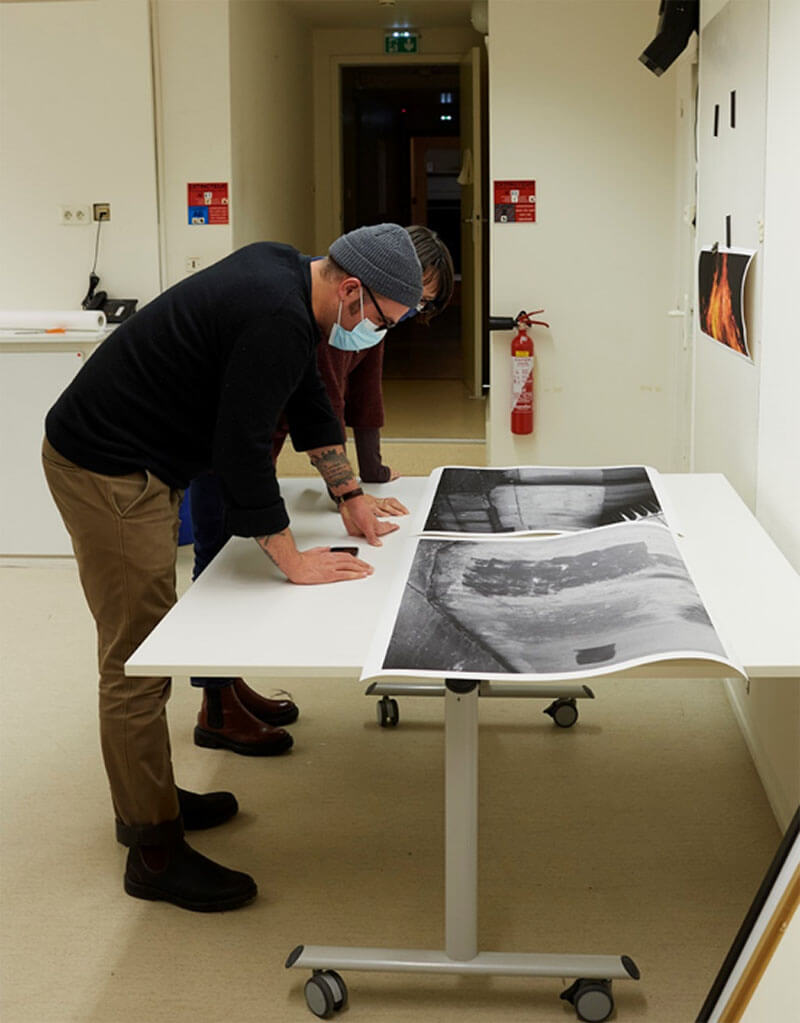

All the prints in the Our day will come were made by the laboratory at the Musée Nicéphore Niépce on ARCHES® 88 digital printing paper.

ARCHES 88 (DIGITAL PRINTING) – Arches Papers (arches-papers.com)

Stephen Dock is a French photographer. He was born in Mulhouse in 1990 and lives and works in Cambrai. Stephen was quickly confronted with the realities of the field with his first subject in Venezuela in 2008. After that his work took him to many countries: Venezuela, Nepal, the West Bank, Syria, Iraq, Northern Ireland, the United Kingdom, the Central African Republic, Lebanon, Eritrea and Kashmir in India.

His approach focuses on a visually studying our ability to build and live in an urban, cultural or political environment. It tries to make the habitual, day-to-day, banal elements of life visible and is particularly interested in the traces left by all types of fracture, conflicts real or latent, class wars or real states of war on our contemporaries.

A member of the VU’ agency from 2012 to 2015, he was a finalist in the running for the Leica Oskar Barnack Award in 2018. In 2020, he was a runner-up for the Louis Roederer Discovery Award at the Rencontres d’Arles. He won the “coup de cœur” prize in the LE BAL Awards for Young Creation with the ADAGP in 2021, with his project La gomme de l’habitude.

His work was exhibited at the Leica gallery during Paris Photo 2018, and has also been shown at the Tbilisi Photo Festival, the Visa pour l’Image festival, at the CNAP, at the MAP Toulouse festival and the Bayeux festival. His photographs have been published in the French and international press, including M le magazine du Monde, Figaro Magazine, Newsweek Japan, Paris Match, Internazionale, VSD and Libération